The main reason I started The Director’s Lens was for personal enrichment and growth in understanding the artform of film. I love movies, I always have. I consider film the peak of human artform that combines all other artistic disciplines: color, sound, drama, writing all blended into a final product that is unique, entertaining and often times very personal to the individuals who crafted it.

While I have seen many, many films, from blockbusters to arthouse indies, I’ve never fully dived into the depths of analysis and appreciation to become a more informed movie-goer who has a basic understanding of film form and technique. As much as I would love to head back to school and pursue a degree in film studies, that time in life has past, but that does not mean I can’t self-create a curriculum to help guide me in appreciating the artform of cinema. So, I ordered Film Art, An Introduction, a classic film studies textbook to educate and reinforce my passion with academic knowledge. I’ll be using this space as a forum for deciphering the various films I’m watching through the lens of the lessons and learning objectives I gain with each new chapter.

We start in the book’s introduction with the most important question of all, why is a film designed the way it is? The answer is key in understanding film as an artform. Throughout the filmmaking process, every discipline lead whether it’s the scriptwriter, director, cinematographer or costume designer, is constantly asking themselves, if I do this, as opposed to that, how will viewers react? These choices will ultimately communicate the information and ideas of the final film. Just a few examples include:

“What lighting will enhance the atmosphere of a love scene? Given the kind of story being told, would it be better to let the audience know what the central character is thinking or to keep her enigmatic? When a scene opens, what is the most economical way of letting the audience identify the time and place?”

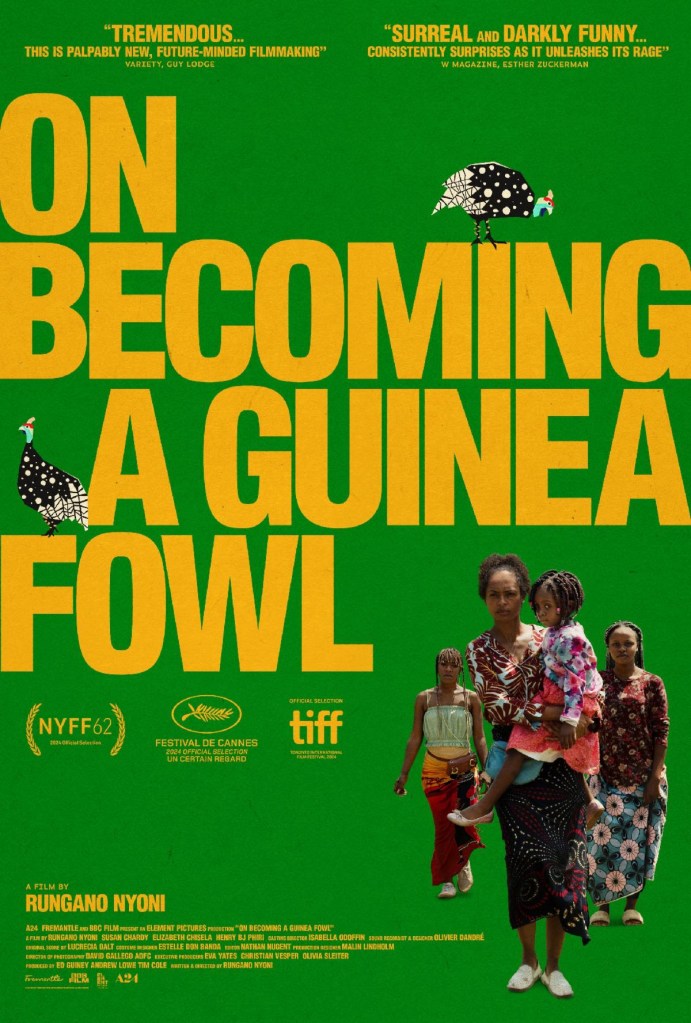

This is where I want to start, identifying some key choices by the filmmakers. Today’s viewing is On Becoming A Guinea Fowl (2025), written and directed by Rungano Nyoni. Before I even begin, just the visual draw of the poster, an art piece designed to communicate the purpose of the film and lure your eyes to ask the question of whether this something I want to see or not provides you with clues to the film. The poster is sparse with a bold title in bright yellow backed by lime green that fills nearly the entire space, with a small image of what appears to be a family, three women with a young child, dressed in African clothing. Simple, yet communicates a concept of a drama centered around family.

As the film begins, it immediately introduces the central character, Shula dressed playfully in a costume choice that alludes to Missy Elliot in “The Rain (Supa Dupa Fly)” music video. While silly, the humor is quickly juxtaposed in the tragedy of the situation Shula finds herself in when she discovers the dead body of her uncle Fred lying outstretched on a road in the middle of the night. After a brief pause as she identifies the corpse, Shula displays no emotion whatsoever as she identifies the body and begins to make calls to the family to decide on the next steps. So much is conveyed in the first 10 min through the choices of the filmmaker and the amount of information given during the first scene that sets the table for motivation, character relationships and the central theme of the film.

The camera work throughout is constantly fixated either on Shula’s face in close-up or behind her shoulders, capturing her emotions worn across her entire body as she takes in all the situations surrounding the death and funeral of her uncle and the fallout from past revelations being revealed. Her blank face an indictment of her family’s performative cries and the tragedies beyond his death that she knows of and has experienced.

Throughout filming, Nyoni often lets the camera stay in place after a scene is completed, characters in a car depart while the audience stays in the backseat sitting in silence as we watch them walk away. Shula picks up her mother at airport and she collapses into her arms with grief, pulling her down to the ground as they go out of frame, and the point of view holds with them gone. These moments provide time to think and question what is happening to our characters and ask why they are behaving in ways unlike the rest of the family we see on screen. Perhaps no better example exists of this directorial choice than the incredible moment where Shula goes to see her father, asking him to help her in providing for her deceased Uncle’s Widow. After a fruitless conversation she leaves, but eventually her father calls her before she exits the cavernous building they’ve met at. The camera catches Shula the moment she picks up her phone before heading out the front door, but we can only see her from the waist down as the rest of her body is cut off by the ceiling. Her father asks a cutting question and after she answers, we see her body language communicating through her stance the complexity of the question and her interior emotion as she holds still, thinking about the call before leaving. The shot lingers long after her feet have left the building.

Music plays a subtle yet important aspect of setting emotion, often with the mere thrumming of an upright bass chord or the ringing of static in various tones. All play for short moments but deliver a sense of danger as when we see Shula’s cousin Bupe arrive unexpectedly at the funeral house after just being admitted to the hospital. Shula must trek through the entire grounds, dodging pestering uncles asking to be served food all while at any given moment Bupe will collapse to the ground.

The decision of the surreal ending has stuck with me the most, only heightened by the foreshadowing Nyoni sprinkles in moments throughout the film. The final seconds on screen arrive like a wave of reckoning that you can see coming from the distance but cuts to black before we see a final confrontation we can only imagine of in our minds.

As I was reading the introduction of Film Art: An Introduction, I was struck by a specific line I always had an innate sense for but never seen written so concisely. “Films communicate information and ideas, and they show us places and ways of life we might not otherwise know.” I couldn’t help but feel that specifically with On Becoming A Guinea Fowl, which so clearly provides a sense of place and culture while wrapping you into a complex and intimate story. Watching scenes play out and being attuned to choices that the director is making already makes it feel like I’m viewing film differently, more critically and questioning. It’s an exciting start to the project that I can’t wait to see unfold.

Leave a comment